The clear, bright sunshine and bright blue of the sky here at the beginning of this Easter Sunday in Southern France is the same as the sparkle of this same day almost exactly one half of my lifetime ago in the gardens of a big old brick home in upstate New York. As I watch two small french children looking for hidden eggs in a backyard I can see from my study window, I’m transported to that other time. It’s powerfully bittersweet, this moment, flooded with the absence of my own children and grandchildren seven thousand miles away, confined in their tiny apartments.

That day so long ago, I had flown two days before with my family of two small children and their father all the way from one coast to the other. It was a momentous trip. It was the grand stage setting for the first time my whole biological family would be together.

We were all coming together at the home where my three brothers and one sister had grown up in the rural area of Rockland County. It was Marvin, my biological father, who had conceived of the gathering, and my biological mother, Toni (whose name I bear like her thumbprint), who had created all the beauty and the magic of the staging. The play unfolded, a work of genius.

We were all converging on the old brick three-story farmhouse they had bought when, in his first years as a doctor, Marvin had decided to move from the city to set up a medical practice. The house had been in tough shape, the surrounding land untended. They managed to fix up the house to make it livable as the family grew. Over the years, Toni had labored to create a landscape of incredible flower and vegetable gardens all around on a property stretching from the house down to a woods and a lake. She had planned and dug and planted and weeded while raising four children, working on a doctorate in history and teaching. Marvin had mowed the lawn on his riding mower on weekends.

These, my biological parents, had already taken turns coming to meet us in our home in Washington state. Marvin had flown out a week after I had called him and we had spoken for the first time. He saw himself as the emissary for my mother, for whom he knew the impact would be earthshaking. She came a week after.

My middle brother had called the day I first spoke to Marvin. My other two brothers and I had spoken over the next few days. My sister, the youngest, was the last. It was to be the most powerful bond.

This was the first time we would all meet together. My two oldest brothers would come from the city, the youngest from Maryland with his wife and two small daughters, miraculously almost the same ages as my own daughter and son. My adoptive mother, Pearl, would come the following day to discover what her place was in all this, she who had raised me and given me the emotional freedom to find them. Marvin was the bridge of warmth we could all cross, the patriarch and healer whose bear hug melted all pain.

I can look back on that day now still as a time of magic and wonder, even from this position on the mountain of life’s difficulties. The big house was sold years ago so Marvin and Toni could move to Maryland to be near their grandchildren and live a simpler life. Marvin has been dead for several years, dying on the anniversary of my adoptive mother’s birth in some mysterious synchronicity. His perfection in those first years we knew each other still lives with me even after the harsher realities of the afterglow. My adoptive mother died years before him. The family was blown apart after the death of their patriarch. My sister, my mother and I have floated this way and that, together though apart, held to each other by the stickiness of women’s love and tolerance.

The day before, Marvin had picked us up at the airport, driving in his off-hand unhurried way, from time to time turning his big wooley head fully around to talk to me as we navigated the congestion from La Guardia, making me draw in my breath and grab my son’s car seat. We turned safely onto their country road after leaving the parkway, seeing landmarks for the first time that I would come to know so well over the years.

We turned in through a gate in a row of old trees and crunched onto a gravel driveway. There on the steps stood Toni, a woman tall and beautiful still. Quickly out of the door behind her came two men who must be my brothers and then a woman, my sister. Opening the car door even before we came to a stop, I stepped out awkwardly after the long trip, almost tripping backwards into the arms of a sister and brother. My children, a son not yet two and a daughter of five, climbed out of the car and up the steps into Toni’s arms, now familiar from her visit as yet another grandmother, their third.

We were ushered through the door into the big farmhouse kitchen with its enormous counter and sloping old floor. It was there that we stood, talking excitedly, greeting, hugging and looking at each other at arm’s length, filling the space with uncontainable energy. There were the big brown eyes, there the long legs, there the unmistakable nose, the chin, the eyebrows. And then, there was the sense of humor, the laughter at each other’s rye comments and a recognition of how that humor typically goes unappreciated.

And then the food, the endless fabulous food! The wine, the noisy conversation and more laughter around the big table in the dining room with tulips from the garden, the big Irish Terrier begging for food around our legs to my son’s delight. Marvin’s tremendous joy in a family all together. His puns. The intense delight we all felt, the cleverness in having found each other. And fitting together like the pieces of a scattered puzzle. And then, tired, tipsy, full of volcanic emotions, being shown up the narrow stairs to the third floor, past the bedrooms where my brothers had holed up as teenagers, into the big attic room lined with shelves crammed with books, with a cozy bed under the eaves and windows overlooking the gardens. My little family all piled into the big bed, and windows cracked open to smell the sweet night air, we all fell into a peaceful, satisfied sleep.

The next day, Saturday, we sleepily met each other at different times in the morning, coffee and bagels and cream cheese in hand, beginning the interchange that would go on for days, learning about each other as people do when falling in love. My sister and I spent a precious hour lying on the grass, talking about all the things we already seemed to recognize in each other and discovering more about the trials we’d endured. My youngest brother arrived with his wife and two blond girls and the children played happily in the freedom of the huge walled gardens. Looking into my youngest brother’s face again and again with furtive curiosity, I was mystified. It felt like such a familiar face, like the face of someone I’d lived with for years. With a start, I realized it was like looking at my own face, into my own eyes, in the bathroom mirror.

Lunch was outside where we all sat on old wrought iron chairs and ate grilled chicken, studiously charred by our father, with our fingers. My sister, mother, sister-in-law and I gayly dyed hard-boiled eggs all afternoon in the kitchen and Marvin drove to the airport to pick up my adoptive mother, Pearl, who he was meeting for the first time.

When she arrived, she too was astonished and absorbed for hours, finding all the resemblances, asking her endless questions about their lives, laughing heartily at silly jokes. Marvin and Toni toasted her several times in gratitude for all she had done in raising me and for her generosity of spirit in what must be a web of complicated emotions. She had adopted me at the age of forty. Toni had been twenty-one at the time. She fit into the family as if she were a grandmother, with a comfortable click. They all loved her with her Brooklyn heritage, her love of literature and the theater and her good humor. We were all in love. The memories shine with it.

Easter day dawned. The sun was with us. The sky was without a cloud as I peered out through the curtains next to where I slept. The stagecraft was still holding. Slithering my way over the children, leaving them sleeping, I went barefoot down the stairs to the kitchen to meet the others for the egg hiding. The men didn’t seem to be up, but together the women of the family each took a basket and went out into the damp grass to hide eggs in the most perfect egg hunt setting one could imagine.

Making sure to leave many where the two youngest could find them, we made quick work of it, hiding them among the beds of tulips and daffodils, in the bushes and in the long grass, giving the older ones some challenges in the woodsier places. By the time we got back to the house, the kids were up and being fed in their pajamas.

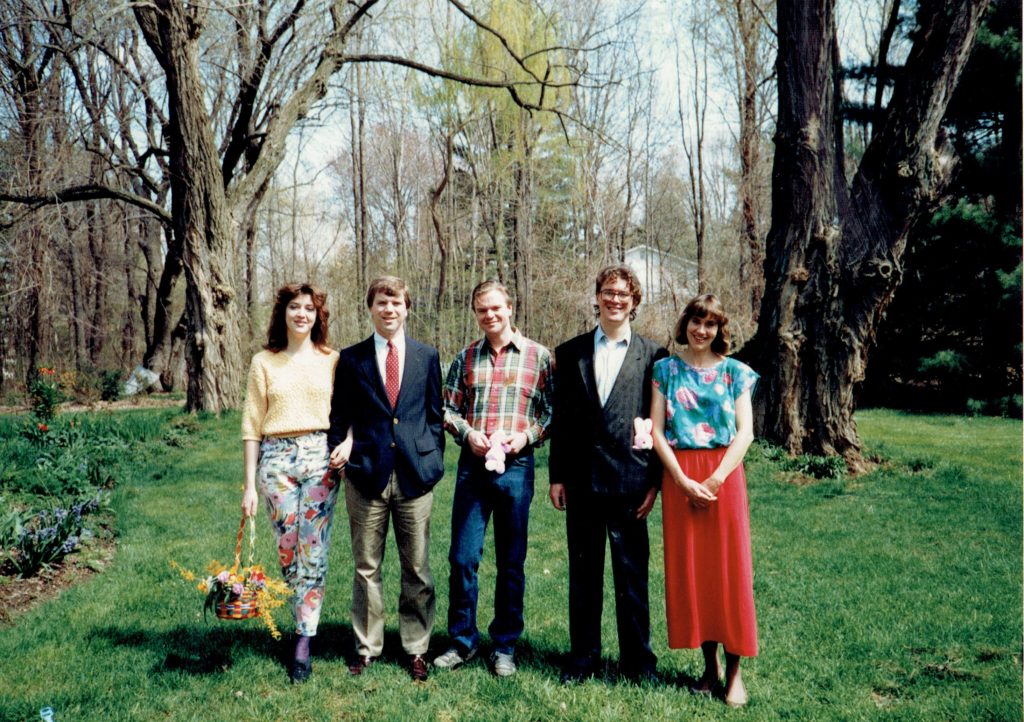

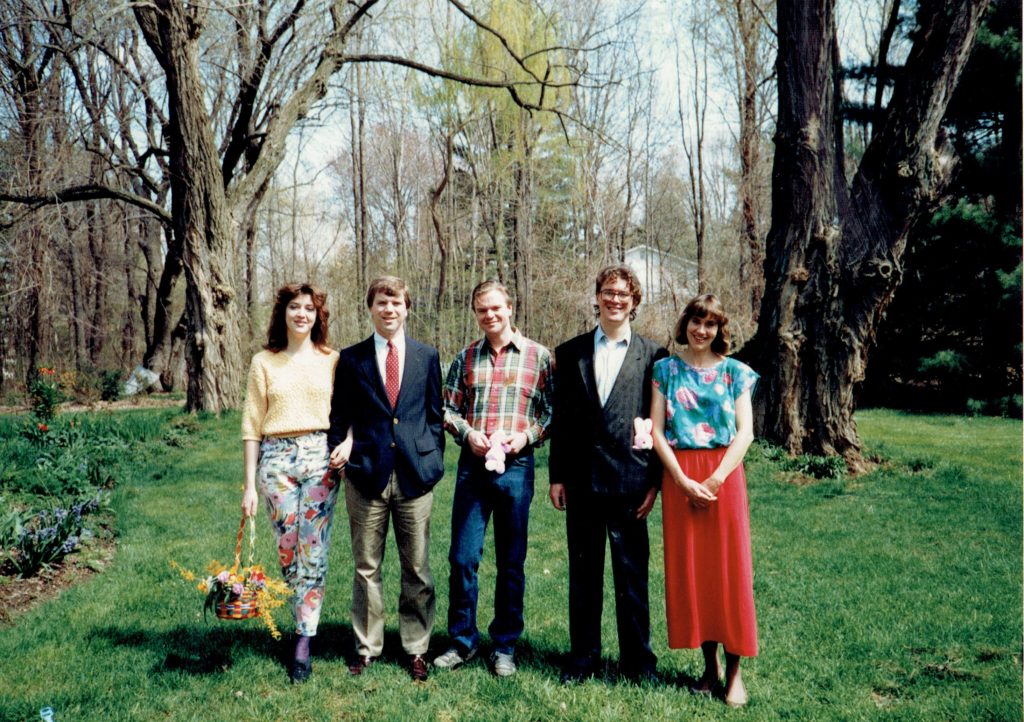

But we were going to do this right, as it should be done. When they had eaten enough, they were led upstairs to be dressed by their mothers in their best dresses (and my son in a new shirt and fancy shorts) for the Easter Egg Hunt. There were photos in the morning sun. Photos of the children posing with their hair combed and outfits perfect. A photo of all the siblings in a line. A photo of the youngest girl, so blond, so mischievous, eating a whole painted egg from her basket, crunching it shell and all. Photos of the various configurations of parents with their children, my ex-husband looking a bit quizzical or perhaps a bit stiff or bored, awkward as all this was for him, whose culture was so different.

The best of these photos hang on Toni’s wall in her room in the Assisted Living where she moved just days before everything changed. My sister hung them there right before that novel virus burst on the scene and made us all bow down. My last (and first) mother’s been confined in that room now for the last three weeks. She’s taking it all well, reading avidly as always. It’s good she can’t watch the news on a TV that won’t function. Her mind is sharp, her admirable intellect intact despite the things of the moment she easily forgets. We are all on pause. There was some error in the programming, some glitch we now must all endure. She waits–for what, she doesn’t know.

So much has happened since that bright day. The fairytale does, indeed, shift with the often grim realities of families and time. The story has become more of a novel by Tolstoy or Chekhov than a Hans Christian Anderson confection. Strangely, all of this has blended into some kind of experience of family, incredibly rich, intensely joyful and intensely tragic.

But those days of clear sunshine persist as one of life’s true beacons as I sit here in a room so far away in time and space and texture, wondering, quiet.