When I’m walking I’m happy. Even if I’m feeling miserable, I can feel the misery full on, I can have a talk with it. It can do its real work.

This morning in Garsdale it was clear enough to hang out the wash. By one o’clock the rain had returned and the laundry had to be brought in to finish drying by the heater. But even with the rain coming down, the weather is much more tame than yesterday’s when we were walking across the fells from the village of Malham near Settle, winds of sixty miles an hour or so driving rain and hail across the moors, sheep standing in depressions near the drystone walls to ride it out.

The walk to Malham the day before had been wonderful. Despite predictions of rain all day, the rain came in bits and the sun came in and out, the wind gentle, driving the clouds in their various forms and shades of grey, cloud shadows running across the spectacular vistas of hills and dales with their craggy limestone cliffs and outcroppings, over miles of vast green squares marked off by miles of drystone fences, white and grey and brownish. The rain pants we’d bought that morning kept us dry in the wet spells. Some of the territory was familiar from a walk a week before from Settle–satisfying to recognize a tree, a style, a stretch of re-forested land, a lane, a farm, a turning.

Just before reaching Malham, as we made the choice to take the footpath rather than the Pennine Bridleway, my spirits were high, my heart particularly open. We had just spotted the beautiful oval shape of the water of the Malham Tarn, as lovely as any lake, I’m sure, that I haven’t yet had a chance to see in the Lake District. The sight of it had lifted me further.

Checking the map together, a bit tired, we had a bristly moment of interaction. On the trek down the hill to the village hidden by trees in the bottom of the cup of the wide valley, I had the time to walk with the dis-ease that had suddenly surged up in me, feeling it molded by the effort required to find footfalls through rocks and mud on our downhill climb, softened by the vast beauty of the surrounding hills and cliffs.

This is the beauty of walking. It took a while to make out the actual buildings of Malham, nestled as they are in the greenery by the stream of the Malham Beck. By the time we were close enough to recognize the charm of its setting, the beauty of the stone houses with flowered gardens, the trees bending over the trickling water, I had digested the pain of the emotion enough to understand its origin. We would soon be leaving this countryside, this place where we had come to feel settled for a time. We would be leaving Europe and returning to the US to grapple with the difficulties of immigration, both technical and emotional. Upheaval. Like the motion of the tectonic plates creating the landscape. Ah, yes… My old friend that rumples me, always.

Thirsting for a British beer, one of our last, we headed directly for the inn overlooking the beck, the one over the stone bridge where a willow leans over the bank. It was warm enough to sit outside by the stream, drinking Bitter (which is actually creamy and smooth), feeling luxurious, enjoying the hum of our bodies after their exertions, drinking in the beauty all around us, surprised by the sight of tourists gathered in this isolated spot. The distress that still smoldered was cooling, no longer needing to sear to do its work.

After we checked into the hostel down the road and had a rest in our bunks, we came back for a lovely dinner at the same inn by the water. Checking our weather apps, we discovered that severe weather was predicted for the next day, our walk back to Settle. A big storm Ali, the first of the season, was blowing across the northern part of the islands from the tropics. Eighty-mile-an-hour winds were forecast. Big rain. No one in the village seemed the least concerned.

We went to bed and slept well, dreaming the many dreams as we do every night here in the quiet and calm of the Yorkshire Dales. We agreed to wake up and decide then whether to continue our walk or take the one bus a day from the village to the train station at Skipton. We figured we’d walk if the morning looked at all decent.

It dawned warmish, breezy, grey and dry. We had our breakfast and picked up the packed lunch we’d asked for and set out on the “top” part of the circle walk back to Settle through Malham Cove. Why not try it. As we started out, I had no conception of the beauty we would see in the walk through the cove, nor the wildness of making our way over the high moors in high weather. We watched as a large group of walkers started out over the first part of their walk, evidently prepared, as we were, for anything.

The walk away from the village gives a deeper sense of why it has settled into its nest there in the cup. There it is protected by the trees gathered around the water, sheltered by cliffs and hills at the edges of the bowl. Having had a life there for so long, raising its sheep and cows, mining its limestone, it has blended into its landscape with the sigh of a weary body sinking into a cosy bed.

So nearby, less than a mile of walking over the Pennine Way through lanes and then fields, the limestone cliffs that surround Malham Cove begin to rise up. Just there, dwarfed as you feel, you can see how the little river flows directly into the parting of the rocks. Around the cove, the land becomes a park of green grass, oak and rowan trees, dotted with limestone rocks of all sizes, looking tended yet wild.

For awhile we explored the deep canyon and the waterfalls seeping between the feet of the high limestone cliffs. Eventually, we found the bridge of field stone slabs that takes you over the swollen stream to start the climb up the huge rocks of the other side of the cove. The way is made easier by a seemingly unending flight of huge limestone steps that wind their way along the side of the rocks, their scale like something made for a race of primordial giants, each turning presenting yet more shifting pictures of the widely winding valleys and softly rising hills. Winded, we paused several times to breathe it in.

And then, unanticipated, not indicated on our map, one or two last turnings before the true top of the fells, we came upon the stretch of enormous, flat limestone rocks called a Limestone Floor. Protected from the wind and rain and foraging sheep, rare plants grow in the narrow crevices between these gigantic slabs. The sheer expanse and flatness of it, spreading towards the cliff edges and the horizon, gives a sense of the infinite. We walked from rock to rock for a bit to see more of what lay ahead, but the going was precarious enough to better be left for younger legs.

The weather was holding as we climbed over one rise after another and came to the turnoff to Malham Tarn around a limestone outcropping. A couple whose path had converged with ours turned that way in the building wind. We kept on across the fields to follow the Pennine Way back to Settle, saving the trip to the lake for another day. So much of what we do now contains the piquant sense of a last experience of the place, greeting and parting at once. With places like these, I at least like to pretend I will return. There is so much more.

As we took the left and began crossing the next field to the gate over a road, the rain began. After climbing the first hill up to the high plateau of the moors, the wind was beginning to push the rain it in its characteristic gusts across the fields. Time to stop and put on rain pants before we got truly wet.

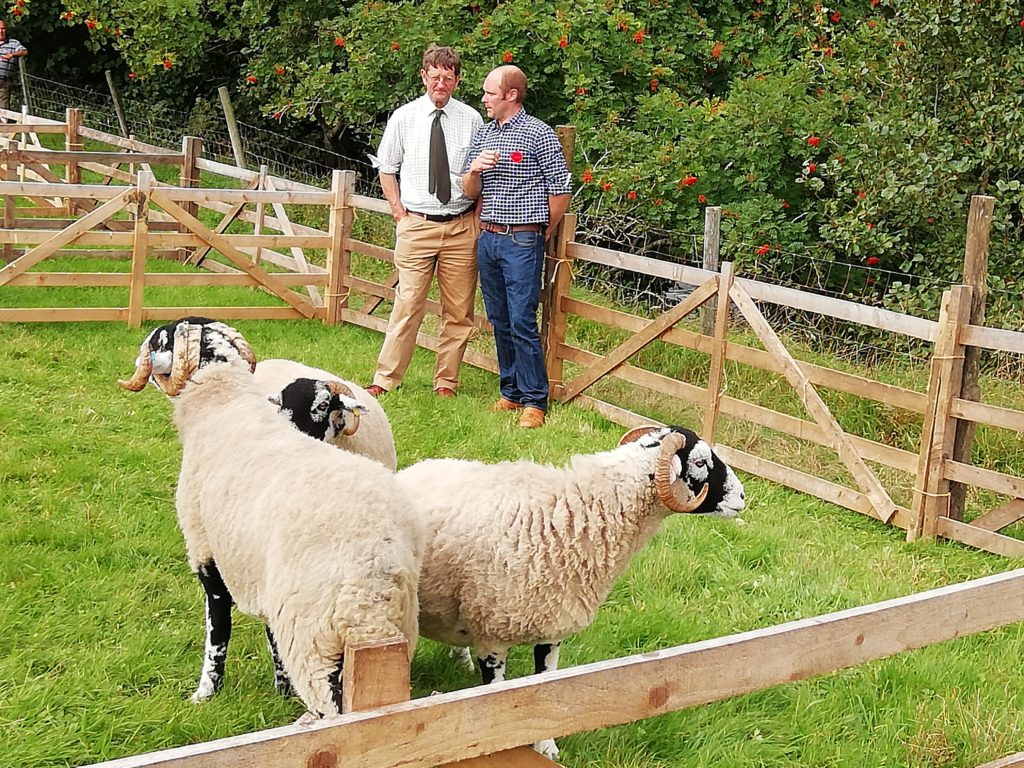

We took off sweaty shirts and put on a couple of warm layers. The best would have been wool next to the skin but I at least had a good mohair sweater to put on top of a dry shirt and Walter a fleece. As we tightened our boots and pulled on our wool hats, the wind was beginning to gust with real strength and the rain had started in earnest. The sheep, most positioned now against high dry stone fences or in the gullies, looked at us as we passed, ready to run if we tried to join them, seeming to wonder what we were doing here in such wind. Four miles to Settle.

Here the moors stretched out on either side with little variation. Distant bluffs were hidden in rain and fog. Since I often like to walk faster than Walter, we had a bit of distance between us, a solitary yet linked experience of the walk. At first, still dry and exhilarated from the beauties of the first three miles, the pushing wind had little effect. As the rain began to really pelt and the wind to exert its true strength, the going got a bit harder. But leaning into the wind and crouching down a bit in the most powerful gusts, overcoming a brief moment of a kind of panic, I even welcomed the hail that came next.

We each sang our own songs, the sound of the other’s voice drifting in and out softly, as we put one foot in front of another, the going much slower than before. My feet were wet from stepping into a bog near the last stream and my sweater had soaked up some water through a pocket hole I’d forgotten to zip, my hat was wet, but the wind was not cold. For all its power to push as if to lift you away over the fences and the hill’s edge, it felt like a wind that carried just a tinge of warmth from the place it was born. We trudged on in our singular ways, knowing the other was enjoying the challenge, anxious just enough for the other’s safety to stay close.

Hungry and a bit tired from struggling against the wind, we rounded the corner of a hill the other side of Jubilee Cave, a place in the limestone outcroppings we’d picnicked a week or so before in nicer weather. Then we had sat on the grassy, mossy hummocks with our backs to the cave, enjoying the warmth of intermittent sun and the grand sweeping view of dales to the left and outcroppings to the right. Today, we scrambled into the rocky opening as humans clearly have done for millennia, climbing over pools of water to some dry rocks at the back. Here in the last recess, there was no wind. The quiet was a relief. We were warm and sheltered. We took off wet socks and replaced them with dry ones and shared the sandwich from the hostel. Nothing like it.

Dry and renewed, we climbed out into the still powerful wind that tried to push us back up the hill and wound our way down to the walkway of the Pennine Trail that here goes straight for a way between rows of dry stone walls. The rain had stopped for a bit and the walls gave some protection from the wind. We felt a renewed sense of happiness, a buoyancy. The Dales had given us a chance with a different dimension of their beauty, the power of their wildness.

As we approached the gate where the other path comes down from the larger Victoria Cave, three young women with a couple of small dogs were organizing themselves as they came through a field gate, looking at a map. We asked if they needed help. They were dressed fairly lightly with no hats and seemed unconcerned about the weather. I suddenly felt overdressed and a bit fuddy-duddy.

“Oh, no,” said the one without a dog on a leash. “We’ve just come out to do the circle but on the way up we were attacked by some cows in a field. They were running after us and kicking at us and the dogs. We’ve never seen anything like it! We had to run for the gate. Fortunately, it was close enough to get away and put a barrier between us. Unfortunately, we can’t go back up through that field again to do the circle so we’re trying to figure out whether we want to go up the other way.”

We confirmed that it was, indeed, a very unusual event for cows to attack, especially if they had no calves.

“Maybe it was the wind that disturbed them,” we agreed.

Evidently deciding to call it a day, they trotted off merrily ahead of us in the direction of Settle.

“Hmm,” I said to Walter. “Hearty English!”

As the rain cleared off, the wind dropped and the blue patches of sky began to appear, our jubilant mood spread itself out over the whole landscape. The path down to Settle is beautiful and now felt familiar. You can see the towers of the old textile mill at Langcliff as you turn down to the left along the hills. The limestone cliffs on the hills over the town loom to the left after a quarter of a mile or so and the whole town stretches to your right in its bed in the valley, limestone quarries guarding its flanks.

The green of the fields around you and the misty colors of the distant fells and dales is such a satisfying background to a walk that you feel you could just go on that way forever, thinking of nothing and then thinking of something for a bit, tossing it around, following it in its several directions and then releasing it into the fresh air–being captivated by some form, some color, some particular grace of motion, some particular beauty of light while all else disappears.

I am happy when I walk, even when I’m not happy.