The day had arrived for the Moorcock Sheep Show. The weather was remarkably pleasant. No sign of rain. The air actually felt warm. Tee-shirt weather. Not the norm here evidently, even in summer.

We came to live here in the Yorkshire Dales for a couple of months in the way that much happens for us—through the opening of an unexpected door. We are in a time in our lives when we can wander. So here we are, in a little hamlet without a car, in a cozy little stone house lent to us by friends, dependent on the grace of delivered groceries and on the obscure Settle-Carlisle Train Line that runs by the cottages to get to a town or village of any size at all.

As is always required, we’re tuning ourselves to the circumstances. Harmonizing. Soaking in what is present–the character of the people, the fauna and flora, the beauty of spreading hills and valleys, the geology, the air. The grace of living here is that we are able to explore the Dales endlessly by foot and to chose our moments. As one walker on holiday (one of many walking and walking, day after day, all vacation long) said to me, “It’s cheating. You can wait till the rain lets up and then start your walk!” So, when we’re not writing or reading or making a foray into one of the towns up and down the line, we do.

Although it is just down the A684 about two and a half miles from the Railway Cottages by car, it would take us over an hour to walk to the show on the footpaths over the fells up above the road, but the walk would be so much more pleasant. We congratulated each other on our decision as we hiked with our daypacks over the stone bridge behind the pub, past the small river Eden with its waterfalls, hearing in the distance the continuing whine of the racing weekend motorcycles as they careened down the stretches of the highway below us.

After a very pleasant three-or-so mile walk, losing the path from time to time through the bigger fields and finding it again to climb the varied stiles in the dry stone walls, we arrived at Moss Beck and walked the steep tree-lined lane up to the fields where the show takes place, stopping to gather some plump rose hips along the way.

When we arrived at the top, a young man, looking somehow comfortable (as Yorkshire natives tend to look in most circumstances) in a loose tweed suit coat, a button down shirt and red tie, sat at the gate with an old man who seemed to be there just to keep him company.

As he took our gate fee, he welcomed us, as obvious strangers to his home, with a genuine twinkle of friendliness in his eye. I watched him as he traded quips with Walter. His slim, smooth Yorkshire face contained more expression and subtlety than you would expect from a “country boy”, more ease and confidence, a sense of self without arrogance. The unexpected delight of it hovered and hummed above the lingering exhilaration from the walk. Savoring this state, I took Walter’s hand as we crossed the grounds towards the beer tent. In front of the tent, a brass band was playing “When You’re Sixty-Four” as they perched on precarious folding chairs set up on the uneven grass, the men all nattily dressed in black suits, white shirts, red ties and black hats and the women in black dresses.

The whole afternoon at the show was like that. Surprises. A small opening into the real life of this place. We bought Wensleydale Best Bitter, brewed in honor of the show, from the blond woman pumping beer in the tent and carried the plastic glasses with us as we went to watch the sheep and their handlers, eager to drink it all in.

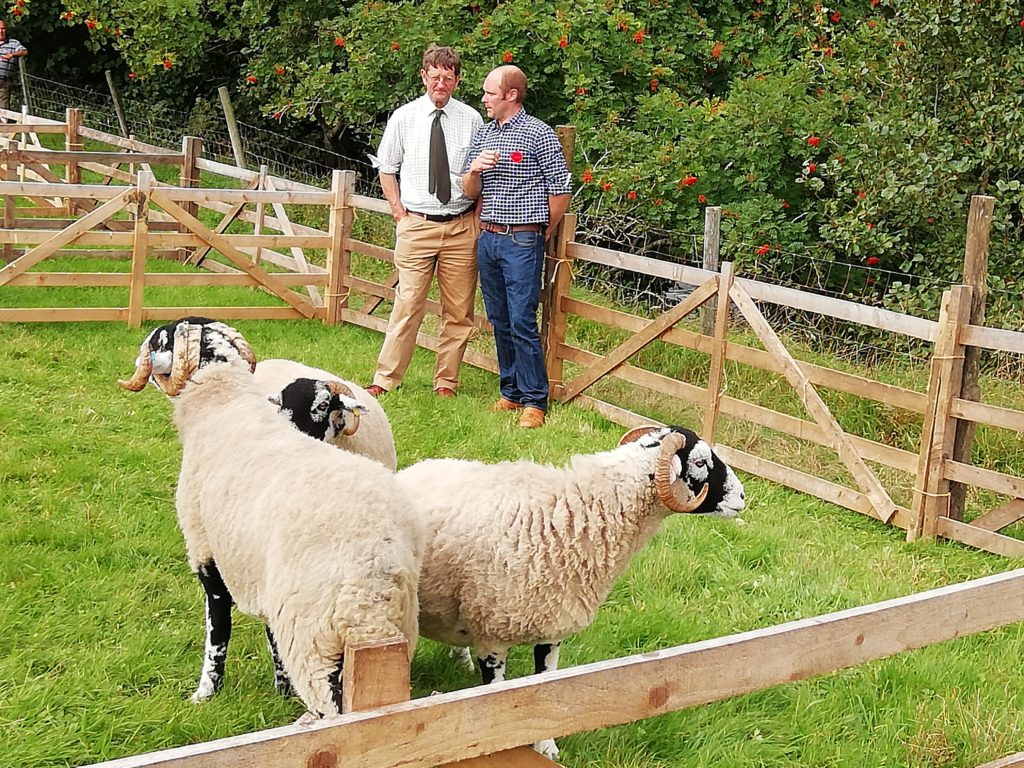

The heart of the show was the temporary pens with their movable sides enclosing constantly moving groups of sheep. Here were young teen-aged girls and boys and their older family members all working together to manage their sheep and show them to the judges to their best advantage.

We watched and read signs, trying to make sense of the action, Walter explaining what he could extrapolate from his own experience. Each breed of sheep has its own “classes”: Tup Shearlings (yearlings after their first shearing), Aged Ram (two shear or above), Tup Lambs, Gimmers (ewes between their first and second shearing) Lambs, Pairs of Tup Lambs, Ewes (Small Breeder), and just plain Ewes. Even Walter, who had grown up with Future Farmers of America and knows quite a bit about raising and showing livestock, was amazed at the wealth of detailed knowledge represented by all these farming families, some judging and some showing, all here for one purpose. Even amidst the air of celebration, an atmosphere of activity and subdued excitement, it was a no-nonsense event.

The first pens held the Texel sheep, an animal bred for its remarkable muscle development and lean meat. I learned later it was a sheep originally from Francw which had then been exported to the Netherlands, New Zealand and Australia and then back to England as a hardy animal able to roam long distances, require little care, lamb without assistance and grow to marketable weight quickly. It’s a white-faced sheep, with no wool covering the face, often with a charming big wrinkle in its nose. When we’ve seen them on our rambles through the dales they sometimes look at us with expressions like those of friendly but suspicious young dogs. On one of our long walks out through the countryside, we’d found a ewe with her head stuck in a fence made of big wire mesh. She had evidently been there for some time, bleating, but it wasn’t until we slowly walked up to see if we could help that she reflexively pulled backwards, easily freeing her head from the noose. Wonderful animals, but likely not as intelligent as dogs. These were beautiful beasts in the pens, wool fluffed and died a light rosy brown to accentuate their colors, magnificently proportioned. The young men managing them in their pens were clearly happy to show them off to admirers–and to be admired themselves.

Then there were the now familiar Swaledale sheep with curling horns that remind me of the wild Mountain Goats back in the Rockies. They’re the sheep we see on all our walks from the cottage, with their black faces and white noses. Up here in some of the highest parts of the Yorkshire Dales, they are easily able to over-winter on the fells. Like the wild Mountain Goats, both the ewes and the tups have curling horns, although those of the tups of both the wild and the domestic are much larger. On our way over to the show, we’d even seen a ram looking somehow mythic with two sets of horns. They scramble over everything, and their black and white faces lifted in mild curiosity have become the characteristic greeting as we walk along the footpaths through the fields.

Since they are our neighbors in the fields spreading out around the Railway Cottages, I’ve tried to learn more about them. Named for the Swaledale Valley near here, they are used primarily for their meat which is of good quality both as lamb and mutton. I think I’ve even bought some in the butcher shop in Settle. Their coarse wool, known for its durability rather than beauty, doesn’t command a very high price but is used for carpets, rugs and insulation. The ewes, very good mothers who can raise lambs well even under harsh conditions, are also used to breed the Mule Sheep, here often crossed with Texel tups. We saw some of these Mule Sheep in the next pens, blue and black faced with wool of good quality, good hardiness, good meat, and ewes that often birth twins—a huge advantage to the farmer.

Finally, we moved on to the pens with the Herdwicks with their white woolly faces and greyer bodies, looking like the iconic sheep that they have become. Something about the width of their faces and the set of their eyes makes them look particularly appealing. We hadn’t seen any of these on our walks. It turns out their genetic characteristics are specialized for the conditions of the Lake District, a region quite nearby here but geologically quite different. Due to its origin in violent volcanic activity, the primary rock there is granite while here in the Dales, once under the ocean, there’s abundant limestone. There the granite, which takes much longer to break down into soil, created a terrain where lush grass is much harder to cultivate. The Herdwicks have been the sheep of that region since at least as far back as the twelfth century, able to graze (as we soon learned) even on lichen.

As we admired the Herdwicks, we remembered together how we’d recently discovered they were Beatrix Potter’s favorite sheep. She, in fact, had become the first female elected president of the Herdwick Sheep Foundation, a mark of the high esteem in which she was held by local farmers of her beloved Lake District. What we didn’t know at the time was that she was an expert mycologist, self-taught, highly insightful and curious, who had become fascinated by fungi and lichens at an early age. Because of this passion, she learned to produce highly detailed, accurate, full-color drawings of the specimens she found on her walks around the countryside where she grew up.

Her idea to create the richly illustrated children’s books that made her famous came only after the rejection of her work on the dual hypothesis of the nature of lichens (called “On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae”) by the all-male Linnaeus Society. It was then that she recognized that she would not be able to make her way as a scientist in a persistently misogynistic environment. Undefeated, she decided to use her skill in drawing from nature to earn her living in some other way. She followed the advice of an old family friend who was involved in publishing and tried her hand with children’s books.

Remarkably, it was these books, with their exquisite depictions of the animals and plants of the English countryside that, through their enormous popularity, skill and insight engendered the beginning of a conservation movement in Great Britain. Her children’s books and drawings stirred a sense of the importance of Britain’s natural heritage Britain in the same way that the writings of the Scottish-American naturalist, John Muir, did in America. Both are considered parents of the conservation movement of the twentieth century.

In her late thirties, with an inheritance from her aunt and the money she’d made from her astonishingly popular books, she bought Hill Top Farm in the Lake District a place she’d gone frequently for the holidays of her childhood. There she dedicated herself to living simply and caring for the land, the flora and fauna, and the sheep that depended on it. While managing her large and expanding farm, supporting efforts to save the rare Herdwick breed, and continuing to write her children’s books, it was at Hill Top Farm that she was also able to return to research in mycology, her original passion. Walter, who grew up without the delights of children’s books (and who developed a healthy scepticism of all things charming) found a surprisingly kindred spirit in Beatrix– someone rejected by the system who, undeterred, continued to pursue observation, research, advocacy and writing in the quiet spaces outside academia. Another surprise.

As we stood there discussing Beatrix and her love for Herdwick sheep, I noticed a man about our age standing near us. He was slim and not very tall and had two dogs on leashes, one a black and white border collie, the other a smaller beagle-like dog. By the look of his face and the ease of his bearing, he was clearly a part of the local Yorkshire crowd. He was in his element, yet his skin was incongruously tanned and, unlike the other men, he wore a small earring and had a decorative cotton scarf tied around his neck. The look was familiar. As I overheard him talking to a couple with their own large dog, I noted that his north country accent was tinged with a familiar lilt, an overlay of the sounds of French. I was intrigued.

As he stood next to us, talking about the sheep to another local, I finally got up the courage to join in and ask a question.

“We haven’t seen these Herdwicks on our walks around here. Are there many in the Dales?” I asked.

“No, no. You’re right,” he replied, the French accent less pronounced. “There are only a very few.”

“Why is that?” I asked.

“Well, they’re specialists in the Lake District terrain. Here on the limestone-based fields, there’s good grass. It’s not like that in the Lake District with the granite. They’re very hardy sheep, can stay out on the hills over-winter and can subsist on eating lichen. That’s the important thing. No other sheep can do that. My brother has the family farm in the Lake District. I grew up taking care of these sheep.”

We settled into conversation. Here was a local who could answer so many of our questions about the husbandry of the sheep of the Dales. We learned about the financial value of the Tups and the Gimmers and what the judges were looking for in the different breeds of sheep.

“The Texel, see, the back legs of the tup have to be thick, strong and long with a good stance extending backwards. That’s not just for the characteristics of good muscle meat but it indicates they’ll be good breeders, able to mount the females on the hills and keep steady. That way they’ll be able to breed with many, many gimmers—thirty or forty. That’s what you want. A ram went for 7000 pounds up there at the farm last week after it won a first. These prizes are worth a lot of money to the farmers.”

“The gimmers have to have a good wide stance in their back legs and be able to stand with the back legs thrust back, like when their standing on a hill and bracing themselves with their back legs. That way they’re firm and open to being mounted.”

“The tups are of course worth three to ten times more than the gimmers. It’s the tups that will breed with thirty or forty or even fifty ewes that will pass on the traits that determine good milk production and the quality of the meat. The ewes pass on the mothering traits.” (This was one of his questionable claims. It is, in fact, true that the rams, because of the number of ewes they impregnate, have more impact on the quality of meat and quantity of milk, but its a numbers game. For the locals, it’s, of course, the big picture that counts. You buy a tup who’s sired lots of tups with good milk production and you’ll increase the milk production of the herd—that is, if he also is strong and mates well, another reason to pay for a good prize ram. )

“See that woman over there in the pink puffy vest? She’s one of the breeders. This is serious business here today. These sheep you see here have already won prizes in smaller shows. The ones that get prizes here today are the best of the best. Those breeders are here to buy. They try to blend in, not make themselves conspicuous, but they’re here to spend a lot of money.”

The conversation worked its way along until we were comfortable enough to get a bit more personal. We mentioned we were moving to southern France. He admitted, then, that he had been living in France himself for more than thirty years. He said,

“It’s a great place to live. You have to learn French, eh? They’ll respect you more.” We agreed.

“I come back here several times a year to help my brother on the family farm. It’s only about a six-hour drive through the Chunnel. My brother calls up and says, ‘What ya doin’? And I say ‘Hangin’ about.’ Then he’ll say ‘It’s lambing time,’ or ‘We need to mend fences,’ or whatnot and there I’ll come. I’m still a local after all.”

As he relaxed, his French accent became more pronounced once again and he began to deliberately slip in a word in French here and there to tease us. As he talked, he managed his two dogs, sometimes speaking sternly to one or the other until they settled again and he could continue.

His story was a good one: a story of a difficult lot that turned lucky. He was the younger of two brothers. When his father died, as has been the case through the millennia, his older brother inherited the sheep farm. Instead of forcing his brother to give him his share of the inheritance, he decided at the age of twenty-one to leave his own share of the inheritance money to his brother so the farm would have the investment it needed to stay alive.

“He’s family,” we said. “He would help if you needed it.”

“Nah,” he replied. “He would, but I’d never ask. I’ve made my own way just fine.”

“I took off to London for college and put myself through. I studied landscape design and agriculture. As soon as I graduated I was lucky enough to be able to do work in my field. A lot of people weren’t so lucky.”

He, in fact, said he had the good fortune to be at the right place at the right time and landed a job doing landscaping consultation for Prince Charles who had just purchased the estate at Highgrove.

“He wanted to expand the garden but there was a wall bordering the estate farm that cramped the area for the garden. I told him it was easy. We would just move the dry stone wall back and make the farm smaller. I assured him we would reconstruct the wall exactly as it had been. He agreed. We marked each stone and moved the wall, stone by stone, back in its place, further away from the Great House.”

When I asked whether he had expertise in building dry stone walls like the ones all over the Dales he said,

“No. I didn’t do any of the actual rebuilding work. I managed the project. I told people here’s what we’re doing and then they did it. That’s what I like doing!”

The rhythm of his story-telling was now in full swing.

“After that was finished, I was told about a farm project in France, in the Champagne district, near the village Epinal, that needed a manager. A friend urged me to apply. I got the job. I’ve been there ever since, almost forty years. I’m not sure how I got it over all the other candidates.”

When I said that I was sure his skills had something to do with it, he replied, “Nah! There were hundreds of candidates more qualified than I was. I’m sure Prince Charles pulled some strings for me. It was political, like most things.”

As we were leaving, a family came by with two large dogs, one quite young, the woman trying awkwardly to sort them out and keep them away from the man’s two smaller dogs. He engaged with them and soon was asking about the dogs. The young one continued to pull at the lead and wind himself around legs.

Our new friend told them that their dogs would soon learn–if they were smart enough.

“Here’s the way you tell if they’re smart,” he said.

“You should always check this if you’re thinking about getting a dog. You can determine their intelligence by whether they have two or three of those long hairs under their chin.”

To demonstrate, he showed us the hairs under the chins of his own dogs. First the border collie.

“See. She’s intelligent. See the three hairs?”

Then the little one.

“Now this one is not very smart. He just has two. He’s teachable but not smart. If there’s only one hair, you don’t want the dog. You can’t train them.”

On examination, the family’s young dog had three. Lucky. They confirmed that he was, indeed, very smart. The other had two.

“Yes. You can teach him, but don’t expect him to be brainy!”

As we parted to go see the Swaledale Sheep being shown, he called out, incongruously,

“Au revoir!”

He and Walter shook hands and as I reached out my hand he, in typical French fashion, pulled me lightly towards him and gave me three alternating cheek kisses. Awkward, missing the cue for the third, I muttered,

“Sorry! I missed. In the Ariege, we only do two.”

“In France, we take every opportunity. We’re greedy! Good luck with your life in France!” he said with a laugh, pulling in his dogs as he turned to walk on towards more friends and more talk.

Who knows about such a guy? Another surprise. In true French (and perhaps Yorkshire) fashion, we never exchanged names but came away friends.

We lingered for a long while, watching the farmers and their families expertly show their sheep, guessing at which would get the red ribbon as first prize, wrong more times than not, learning a lot about the people and their sheep in the process. We ate our lunch on the grass with another beer, bought some cake, a pair of hand-loomed local wool socks and some homemade preserves to take home and walked the four miles back, stopping, of course, at the pub that’s a mile from the cottage for one last pint, some wonderfully hot and crispy chips (French fries) and a bit of chocolate cake.

As we sat together near the window, enjoying the light of the late afternoon and the background of soft Yorkshire conversation in the now familiar room, we agreed that what we had just witnessed was the evidence of a complex knowledge that runs very deep in this culture. It is a knowledge of the nature, breeding and care of sheep, of the land and of the weather, passed on through a few thousand years, for as long as the Dales have been denuded of trees by the people who have lived here. In this place of rolling hills with its intricate network of valleys and the rise and fall of the fells, its winds and its rain, the histories of the sheep, the vegetation and the humans are so closely intertwined as to be impossible to untangle. Each has contributed its breath to this seemingly simple yet complex atmosphere. And now we, too, are breathing it in, greedy as the French for all it contains.

More Photos From the Day:

Enjoyed sharing your day at the sheep show!! Maybe there is an inter-EU competition over origin, however, I have seen the Texel sheep on Texel Island (the largest and most populated island of the West Frisian Islands in the Wadden Sea of the Netherlands), and was told that the Texel sheep originated there (& not France). In fact, we even saw a new lamb being born shortly after coming off the ferry from Den Helder. The local inspector pointed out the shape of the sheep was more stocky with a squarish back side as one of their indicator traits. I know I have photos from that day in one of my photo albums, but not e-photos, would have to search & scan… https://texel.uk/texel-breed-description/

Thanks! Sounds like that should be correct. I think I may have misunderstood my local informant. Glad my post triggered some grand memories!

Well-written post – people need to read more like this, because most info for this topic is unhelpful. You provide real value to people.

Sorry to say I just saw this comment. Thank you for posting. Where are you from? You must know something about the sheep of the Yorkshire Dales!