Though the two mothers met at last when they were past mid-life, the two fathers danced around each other in time and space, never arriving in the same place at the same time, the essence of their life’s blood having mingled at an intersection, unremarked.

On December 7th, 1941 the broadcast of the Brooklyn Dodgers/New York Giants football game on the radio was interrupted at 2:26 PM to announce the attack on Pearl Harbor. One father, Stanley, was twenty-one. The other father–the one who provided me with half of the matter that has carried me around for sixty-six years—had turned fifteen that day. He had lived in a Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn for all fifteen of those years.

Stanley may also have been in the city at the time. He’d come from Pennsylvania a few years before to attend the free socialist college, Brookwood, in Katonah, an hour or so north up the Hudson River by train. He may have been working as some kind of editorial assistant in a comic book publishing house by that time. The college had closed down in ’37. He was working at whatever he could find, for as many hours as he could. It was the Great Depression.

It is unlikely he was listening to the radio that Sunday when the announcement was made. Neither father was very interested in football. If it had been a baseball game, Stanley might well have been spending the afternoon in front of the radio with his stenographer’s pad in his lap, taking notes on the stats of the game, maybe drinking a beer, but it wasn’t the season for baseball.

On that day of his fifteenth birthday, the other father, Marvin, was already attending City College. A young Jewish prodigy, he had graduated from an accelerated academic high-school by the time he was fourteen.

It was highly unlikely he was listening to the game that day. He was probably having a quiet Sunday birthday celebration with his parents and his younger sister. December 7th, the day of his birth, was not yet the historic day it was to become in just a few short hours.

So it was probable that neither heard the live announcement of the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. But both, I’m certain, were tuned into the radio at 12:30 PM the following day when President Roosevelt delivered his famous Pearl Harbor speech to the Joint Sessions of Congress, broadcast over every major radio network in the country. Maybe they both were listening there in the same teaming city.

Marvin may have been at his job as a copyboy at the New York Sun or attending a class that morning, listening with other people grouped attentively around the radio. There might even have been a man in the room with his leg up on a chair, arms resting on that leg, bent forward to direct all his attention.

Stanley might have been listening to a radio in the lobby of the flop-house where he was staying. Or maybe he spent a nickel and bought a cup of coffee so he could hear it while he sat on a stool at a counter. Maybe he bought a beer and listened at the bar, the bartender idle while he watched. It was the middle of the Depression. If he were lucky, he would have been earning five or ten dollars a week. He probably had enough for a cup of coffee or a glass of beer, but just.

Everyone with access to a radio in America was tuned in. Most of the country was listening together when the President gave his address. Within an hour of that broadcast, he was to announce we had declared war on Japan, bringing the US into World War II.

For the rest of their lives, I’m sure both fathers could recall exactly where they were, what they were doing and what they were thinking during the hours following that broadcast. I never heard them speak of it.

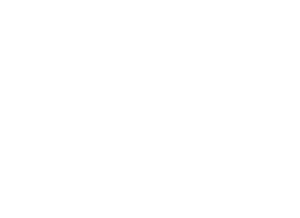

One father I spoke to many nights as a teenager, sitting in the living room in the home where l grew up, my mother the teacher having gone to bed, my father with a tumbler of vodka in his hand, rubbing the torturous scar on his right knee that had plagued him since he was a child. The other I spoke to as a grown up and a parent myself, there in the living room of my own house or at the wonderful dinner tables of his long-time home in Upstate New York, and at his home in Annapolis where he lived for the last years of his life, retired but not. These conversations were never about the mundane aspects of the war years. Not with either father. Now, when I ask the questions, they ascend like smoke into the winter sky.

Marvin was too young to enlist or be drafted. Sometime in 1942, he left his family in New York to finish his college degree. He had somehow chosen the University of Virginia in the alien land of Charlottesville. At age seventeen, in 1944 when the war was still in full swing, he finished his BA. He stayed there to attend Medical School.

Although Stanley was healthy and strong, an appalling childhood accident had left him with no cartilage in his right knee. The leg had never grown as long as the other. Although it hadn’t hindered him much, it gave him a 4F and was assigned to duty in the New York shipyards. He worked long hours there until the end of the war. It’s possible he took other odd jobs in publishing as he could. Determined to be a writer, he had begun to write an article here and there. He had three-by-five cards accumulating in rubber-banded stacks with notes for at least two books.

Marvin was slugging through the first year of med school, making occasional trips back to the City to visit his family.

There in New York, as the war ground on, Stanley started writing in earnest. He worked occasionally as an editor spending the rest of his time as a free-lance writer, sending manuscripts to publishers in big brown envelopes. Somehow, with his head of Cary Grant dark hair, his good looks and his aura as a writer, he caught the interest of someone in a circle of Jewish intellectual friends in Brooklyn. His keen mind and his leftist political leanings gave him validity when his Catholic upbringing and working-Joe status might have otherwise made him invisible to their inner circles.

The mechanics of it all will forever remain a mystery. A blind date was arranged with one of the young women his age in the circle. It must have been sometime in the beginning of 1943. He was just turning thirty.

Marvin was nineteen and approaching the first summer of med school when in May, the war ended in Europe. He was still there in North Carolina in August when the US dropped bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and in September when the war ended in Japan.

In New York, the blind date had turned out well. The handsome young writer from the coal fields of Pennsylvania had somehow made quite an impression. The young Jewish woman was spirited, a year older than he and with a head of luxurious, curling red hair. She was working as a librarian in the city and attending Columbia University at night, trying to finish a Ph.D. A bit intoxicated by the whole encounter, a little dizzy with the novelty, she took him to his first opera, his first performance at the ballet, his first Broadway show. They played tennis.

They got married at the end of the year. His brother and sisters thought he was crazy to marry a Jew. She would be a snob, they told him, someone with no sense of the practical things in life. Her parents were dead. Her four sisters were disappointed. How could he, a product of the coal fields of Pennsylvania and no real higher education , possibly meet the cultural standards of a family of aspiring intellectuals, bent on the highest levels of learning? She was their bright hope and now that light was dimming.

Back in Charlottesville, Marvin was excelling at Medical School. He had found himself to be the only Jew in a sea of other white faces. Even so, he must have had good friends. He played cards with them from time to time. One day, walking past the train station near the campus, he saw a beautiful blond woman get off the train. She was beautifully dressed, slim, self possessed, with the presence of someone who was used to moving smoothly through her environment. He was captivated. And then he saw a friend of his come to meet her. Taking her arm, they walked off towards campus, talking animatedly. He knew he had to meet this woman.

Later that evening, he sat with friends for a game or two of poker. When the friend from the afternoon’s vision came to join them, and talked about the blond friend who had come to visit him from New York, an idea formed in Marvin’s mind. All he had to do was win the next round. Not hard. When he put down the winning cards, he looked across at his friend who he’d just beaten. “Keep your money.” he said. “What I want instead is an introduction to your friend from New York.” They met. He was smitten.

When he was twenty-four, he finished his MD. It was 1949. He packed up and went to do a residency at Montefiore Hospital, back up in the Bronx. The blond woman had finished her last year at the Professional Children’s School in New York and was starting on a full-blown acting career. They must have been getting to know each other better that year, even though her world was as different from his as that of Stanley’s and the red-haired woman’s.

Her family was a family of actors, anomalously Puritan by a lineage traced back to the Mayflower. The two must have fascinated each other. Her blond waves effectively set-off the fine brain they adorned. The blue eyes opened into a world of intelligence. She was poised and spoke with the refined accent of a well-educated New Yorker. She was continuing to act at places like the Buck’s County Playhouse along with well-known actors. And then there was this serious yet funny man with his mop of dark hair and brown eyes behind black-rimmed glasses, his heritage from the shtetls in the Ukraine, his aunt even at that moment, helping to form the state of Isreal and its first kibbutz. She, the blond progeny of a family well established in the colonies by the time of the Revolution, had started acting as a child. Her brother and sister had followed her. She retained her Puritan heritage in work ethic and stoicism only. He was Jewish in values and family only, having replaced his religion with his intellectual passions, but it still marked him as the patriarch he was to become.

Stanley and Pearl were doing well, surrounded by friends old and new, rent parties and work. They wanted a child. She had a series of miscarriages, maybe a result of the stress of working all day and going to school nights. She had contracted TB from a cousin who moved into their crowded apartment when she was twenty. It had weakened her. He was still working at a comic book publisher, hoping to move up from there into more literary circles. Sometime in the late forties, Random House hired him on as an editor. He was on his way.

The lives of the two men were circling around to their nexus.

Marvin courted the beautiful blond. It was one of those things. He was an older man at twenty-four. He was the pride of his orthodox Jewish parents who hoped for him to marry a nice jewish girl. She had parents known in Hollywood, with a big house in Brooklyn and a country place in Vermont, living a flamboyant life, more concerned with their friends than their children, mingling with the movie and theater crowd.

There must have been some moment when the attraction of body and mind overcame common sense and culture, as it has done an infinite number of times over the course of human history. It’s the stuff poems and dramas are made of. Impossible for even culture, with all his power, to overcome that urge.

It may have been right then that the right egg and sperm joined. If it was September of 1950.

Around this time came yet again another miscarriage for the redhead woman living in a small apartment in Flatbush. She was almost forty. Now Stanley had a decent job. She was teaching. It was now or never.

She lied about her age. They chose a Protestant agency. Maybe she wanted to find a baby of less ethnic origin to please her husband’s family. Who knows?

Marvin’s parents had finally met the woman he loved and had shown their disapproval. She was, after all, a Shiksa. And she was an actress they had even seen on television in a live broadcast drama. Not only did she act, but she had played a character who drank. They had plunked a glass of vodka down next to her plate as she sat at their dinner table for their first meeting.

The joining had happened. A baby was on its way. They lived together secretly in an apartment just a few blocks from his parents. He did not want to start a family by being disowned by his own. If only they were “unencumbered” he thought his beloved parents would finally approve in the end. It was a choice between the survival of their love and the baby. She was desperate to preserve that love, he to keep the love of his parents as he kept hers. They married, as they lived, in secret and, trying not to think about it too much, determined to give the baby up for adoption.

The agency interviewed Stanley and his Jewish wife in an office in the posh old brownstone building on the Upper East Side. They admired their level of professionalism and education. They appreciated their energy and good looks. They had them agree in writing to baptize the child in the Protestant faith. Anything, they said.

Meanwhile, the pregnancy was beginning to show. Perhaps his parents, living quite close by, found out and decided it best to pretend it didn’t exist. Referrals were given by friends. The agency on the Upper East Side was known to devote itself to finding good matches for babies of good parentage. It was Protestant. Her family had the pedigree.

June of 1951. A baby was born. A girl. Brown eyes. Blond hair. The nursery at the New York Hospital was being painted. The baby had to stay with its mother, being held. For a whole week. Even though it was leaving. Even though the pain of separation would become so much more acute with each hour, each minute, they passed together. It had been agreed. The papers signed.

At the end of the week, the mother numbly dressed the baby, wrapped her in pink and white blankets and handed the bundle to the father. He drove to the agency in a taxi with a black bassinet with handles which he wedged in lengthwise in the passenger seat. He took the bassinet out of the cab, walked it up the stairs of the brownstone that housed the agency and handed it to a social worker. Sometime that day, the social worker drove to a small house in Brooklyn, carried the bassinet up the front steps and handed it to a woman who met them at the door. The woman went inside, cooing to the baby.

From time to time, Stanley and his wife were told about possible babies. Things weren’t fitting quite right. A few months passed. They were becoming a little worried. One day in early September, they were called into the agency. There was a particular baby the social worker wanted them to see. They were guardedly excited. The agency thought this could be the right fit. Educated parents, one Ashkenazi Jewish, one Protestant. Grew up in New York. Match. Match. She even looked, the social worker thought, a little like Stanley around the eyes, the slightly olive complexion.

Unknown to them, the mother had been overcome by a depression after the birth and separation. Who knows what the baby had felt at leaving. It probably cried unconsolably when it found it could no longer smell the familiar smell, feel the familiar touch of that skin it had come to know against its own. But then it was held again and a different hand fed it and the memory quickly dissolved. The mother struggled to resume life. She felt like she was drowning, locking herself in her room at her parents’ house for almost a month.

But that same year, in September, Marvin and his blond wife, Toni, had a real wedding. Her parents paid for a reception at a high-class hotel in Manhattan, Few knew they had already been married since March. His parents came. They were openly disdainful but kissed the bride. Her mother was there, dressed beautifully. An open life of family had begun.

In the winter of that year, the other couple stood over the crib at the agency, enchanted by the baby with brown eyes who smiled at them and seemed to laugh. No other babies there that day were smiling. Yes, they said, that one. We want this one. Pearl picked her up and cradled her. The baby smiled at them both.

Several days later, the call came unexpectedly on a Friday afternoon. She’s ready. Come pick her up. By the time they had reached to the Upper East Side on the subway, it was almost sundown. They picked her up in the bassinet, wrapped in blankets, warmed with a cosy wool hat knitted by the foster mother. There were a few cans of formula in a bag. The Sabbath had begun in their neighborhood in Brooklyn. No stores open. No baby food. No baby spoons.

Stanley and his wife brought her home to the high chair and crib in the living room of the small apartment. The new mother mashed a banana and made some winter squash. Stanley fed the new baby from the only spoons they had—tablespoons.

They raised the baby, giving it all they had, all of it, their health and their sickness. They told her stories about the other father, the other mother. She knew always that she was other, but not. That father died of cirrhosis of the liver the year his first grandchild was born.

It was thirty-five years after the child’s birth when the first father knew the other father had existed. Then, this first father learned to dance with the ghost of the second.

Meanwhile, the two mothers eventually looked each other in the eyes, their emotions unfathomed by the those who had arrived only later to the dance.

I absolutely love this. I want to know much more about Pearl and Stanley.. what amazing people!!!!!

Written with such love, compassion and generosity.. not to mention skill!!!

Thank you for tjis!!!

Beautiful writing. Lovely descriptions of Stanley and Pearl both of whom I was very fond! Xx

I’m so glad you enjoyed it. Yes. I am grateful they were the ones who found me! I apologize for my delayed response. I haven’t been able to access my comments till I updated my software. Have a Happy New Year! Come visit!