Here we are, somehow settling into the village of Fa, near the small town of Esperaza in the Department of L’Aude in south-central France. As you make your way around the surrounding countryside, you can always tell which way is south by orienting yourself to the mountains or to the tallest hills, the beginnings of the Pyrannees.

We arrived on June 16th when there was still a cover of grey clouds, the days were cool and the locals were still complaining of the long, rainy spring. Our friend from three years ago (met through a connection to sustainable gardening on FaceBook, of all things, a woman originally from Malta who grew up between that island nation and another island nation–England–and moved here some twenty years ago) with a generosity only to be described as “genial (fr meaning fabulous, etc)”, put us up in the little stone cottage beside her pool. In the US, we would say it has two stories. Here, we have a room on the “premier etage” with windows that open out on a view of the garden and the 14th Century stone church that forms the heart of the village. From our bed, we can see what’s happening in the little plaza around the church and hear the goings on from the one cafe restaurant in the village, just on the other side of the bridge over the River Aude, which runs like a big stream through the village.

The sun came out a few days later and on this eastern side of the foothills the summer hit with with an uncommon sudden grinding of the gears. Where the River Aude widens, the cafes of the neighboring town of Esperaza filled. The petanque players came out in force on the graveled spots along the roads of the small towns and villages of the area, their silvery metal balls clanking and shining in the glinting sun of the late afternoon, murmurs of conversation and grunted exclamations of triumph or displeasure wafting by in puffs as we passed. Our work in our friend’s beautiful garden became almost impossible after noon, even in the relative shade. The mourning doves’ cooing and calling took on a new fever in the early morning and later afternoon. Life had shifted.

School was still grinding on. Our host, not only a sustainable gardener but a teacher in the local schools, continued her work despite the shift in the weather. Students were sitting for their Bacs, teachers bored in the afternoon heat, questioning and questioning. The roses, in their full flower in the village gardens, were beginning to wilt around the edges. The herbs of St. James Day, the St. John’s Wort, the Feverfew, the Pis en Lit (Dandelions) were in their full ripeness, ready to be gathered in the fields and forest edges.

On Thursday evening the 21st of June, the eve of Summer Solstice, festivals of music took place all over France. In countless cities, towns and villages, local people had been practicing and preparing for the event. In Fa, on the green common space by the river, a big tent was set up, beer and wine and food was served and almost everyone from the village and the two or three that make up the rest of the Commune were present for some part of the night. In addition to our hosts, we’d met several of the local people, some French, some ex-pats from England and Germany, at the Cafe de Fa in the village. It sits right at the turn off from the main road that runs through the village, right at the bridge over the river that divides the upper and lower village.

Old village houses line the main road, as they do in every village in this region, their wooden doors painted in various shades of blue and red and brown, their wooden shutters often closed to keep out noise and heat. There, right at the turn off to the bridge where large pots of flowers bloom, a young couple have fairly recently taken over the old restaurant. They moved into an old barn up the village road where they are making the most of their youth and energy to fix it up and create something of beauty and simplicity. They are using local food and herbs and cooking dishes of the region and dishes of their own creation. They are making a go of catering to both the expats and the locals while still attracting the flow of tourists that come in the summer. Both speak English fairly well. They work hard and know that the relationships they make with the village and their customers are just as important, if not more so, than the quality of food, wine and service.

They visit with us. They know most of the people coming and going. They know their predilections. They open in the mornings for coffee, some pastries and a few special items. Sometimes they close for a bit and then re-open around noon for lunch. They close around 2:30 and open for dinner again around 7:00. They are closed Mondays and Tuesdays. During the summer, they have live music on some Friday nights, heard by most of the village until midnight. On Bastille Day, there will host someone who will speak about the history of the village, a long one. There is no schedule of opening times on the door. You have to know.

We had already watched several World Cup games with some of the locals who still have an interest in football and a few of the ex-pats. The people of the area are fairly tepid about Le Foot. It is an area crazy for rugby. At the Restaurant de Fa they couldn’t show some of the games since the broadcast package that contains all the World Cup games was prohibitively expensive for a small village restaurant. But when there were games to be seen there was still a mixed gathering in the indoor seating, drinking Estrella beer from Spain, glasses of wine or Syrop with water, chatting during the boring parts and cheering and commenting when things got exciting. People came and went, kissing on both cheeks as they entered, greeting ‘Manu, the owner, Julia coming and going with orders for the customers outside by the river.

We saw them all down by the river that night, many dressed up incongruously in colorful clothes made of African materials. I’m still mystified by much of the symbolism of what I see, just as I am by a language whose delicacies (and indelicacies) of usage I’ll be deciphering for some time to come. As we walked down to the site of the festival in the common area in a shady spot by the river, past the big communal recycle bins, a group of men and women dressed in bright green homemade tunics were warming up in formation, faces theatrically serious and blank, with their hand drums, sticks and shakers, their conductor instructing them with her arcane hand signals. We bought our wine and beer at the stand under the big shelter, used for village parking on other days, paid deposits for the plastic cups, and watched as the troop in green started up, playing and dancing like some small, basic version of the Indian Bands at Mardi Gras.

They went on for what seemed an hour, people, men and women, some almost as old as we are, probable transplants to L’Aude, dancing wildly and beautifully to the endlessly shifting beat. The whole thing, performance and participation, was like something from another time, another space, some of it ancient, some the current reiteration of the ’60s, grown right from this tiny village, a mix of ex-pats, French from other parts and natives of Fa, an exotic stew, with sophisticated flavors and a rich broth. From time to time it seemed that one or two of the elders of the village, those who sit on the benches near the bridge in the evening, came to walk through or sit and watch. They know all about it. Their village is still here.

After what seemed an exhausting length of time, the band somehow still seemed fresh and ready to continue all night. And after other groups played in the tent, there they were again, ready for another round, the dancers from the village following right behind. The church bells had struck eleven times as we walked the short distance back to our little stone house beside our friend’s little swimming pool.

The night still had some good heat left in it as we passed the stone church, the three-quarter moon swaying in the dark blue sky above the bell tower, the planet Venus as bright as an approaching airplane as we walked towards the west where it gleamed in the vastness. We opened the big metal gates and made our way across the grass now wet with dew to our little cottage. Through our wide-open windows, we heard the music and the voices of the festive crowd well into the night. Our host’s teenage boys and their friends wandered through the garden and messed around on the trampoline well after we’d gone to bed, the whole village their playground.

I woke briefly as the bells stuck twice in the usual quiet of the sleeping village. Their sound, the first peal still startling to me, like a metal pipe clanging to the ground, connected me immediately to the place where I am, where I sleep and begin my days. I was not in our little apartment in Salema, Portugal, with a view of the ocean. I was not in Porto where we slept with a window facing the tiled roofs of houses, spread out to the river beyond. I was not in our tiny apartment in Lisbon where perhaps the man with the handcart might be coming down the street at that hour to collect the bags of garbage left out on the sides of the street. It could be Evora, with the church across from our room in the hostel, but there the peals of the bells were higher and more distant. I couldn’t be our room in Lagos where the streets were quiet until 6 am. It couldn’t be Faro, where it might have been the sound of some rowdy, cheering crowd, celebrating some victory as they made their way home at last that woke me. It couldn’t be our room in a hostel in the Albeizin in the magical city of Granada, where Italian students might have woken me with their late night operatic melodramas as we slept in the shadow of the Alhambra. It couldn’t have been Madrid, where our open window had a view of the walls of the surrounding buildings and the only noise was that of other guests coming back down the hallway. It couldn’t have been Barcelona, where there was silence until the early morning when the metro began to rumble from far down below us in its underground haunts.

Even as they’ve begun to recede into the background of my mind where, in the course of life’s preoccupations, they may no longer register in my consciousness, the peals of these bells have now begun to regulate the rhythm of my days. At two am they tell me, “Go back to sleep. There’s plenty of time.” At 7 am my body now responds with “Yes, okay, it’s time. Up now,” and if I hesitate, there’s the repetition at 7:05 or so, as with the peals at all the hours, in case I missed it. At noon, by the second repetition and certainly by the musical peal of the midi hour, my stomach has begun to signal that it’s time to stop for lunch.

Within this rhythm, the heat of the day seems to almost force me to lie down for a nap after lunch. Many mornings we leave the village by 10 am to drive around the neighboring department of Ariege where we hope to settle. Or, if we’re lucky, we drive to meet our agence d’immobilier so that he can show us some properties.

Then, once we’re far from our apartment in Fa, we have learned if we wait until 2:30 or so when we’re really hungry, every place that serves food of any substance is closed. If we stop for lunch between noon and two at a real restaurant, the ones with the fabulous food, we will be there for a couple of hours, drinking beer and wine, waiting for our food and then waiting for l’addition (unless we make a point to the servers or the maitre d’). So we’ve learned to take along a picnic and stop for a beer somewhere at a cafe. I’m getting better and better at taking my turn driving our rented standard shift Citroen through the narrow streets of the countless villages and the twisting turning mountain roads where cars don’t always stay in their lanes around the curves. When we stop to look around at a village or order a cafe au lait or watch one of the World Cup matches at a bar, I chat up the host and usually one or two of the customers, practicing my French or reverting to English when it turns out, as it often does, that they are ex-pats or have spent time in England or the US.

My French is improving, but slowly. It reminds me a bit of when I was 18 and travelling with my friend Alice, both of us in France for the first time after studying French in school for many years. It was as if my sense of who I am was veiled, my ability to communicate my experience of things passed through a thick filter that left people with only the gross residue of my being, rather than the subtleties that make me who I am. It took about a month of growing friendships and an increasing sense of what it sounded like to communicate in French, what it looked like, how it even tasted and smelled to use these words, this music, before more pieces of my sense of self began to return.

Since my sense of self is quite a bit more formed by this point in life, it’s not so dramatic this time ’round. Now the largest frustration is missing huge chunks of the conversations going on around me, missing out on all this stuff, the tissue and complexity of information and interaction that would give me a key to all these humans, to the way they see the same things I see in some different way. I am gliding over the surface, curious, but my interior sense is untouched.

And I’m surrounded by people whose own sense of self seems pretty established. It doesn’t seem to be a concern. And they like that they live here. They don’t seem restless. For the most part, although they see the imperfections clearly, they appreciate what they have, both by being French and by living in the part of the country where village life and country life is still real. They seem secure in a sense of what’s important—community, family, taking care of each other, living within certain means, maintaining a rhythm in life. This could all be an illusion they create for the daily stage of a small village but if so, they’re good at it.

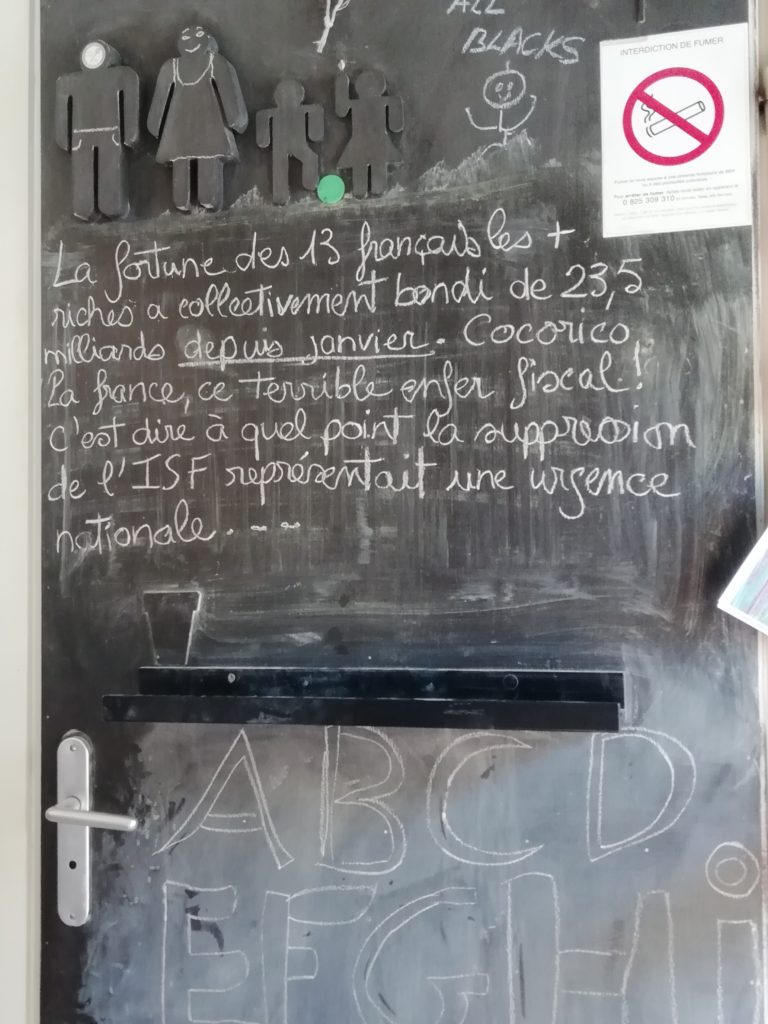

I find I like it. I’m sure that as I get to know them better, their insecurities, their prejudices, their worries, the stresses of divorce, of relationships on the job, in the village, with their spouses and children, their frustration and anger with their government and the world situation, will emerge, just as it does with all humans. Here, they seem to know that all this is in fact, part of being a human, part of life everywhere on the planet and at every time. Although it is an outrage, it doesn’t seem to be surprising. Life goes on. Watch the game. As a man wrote on the chalkboard of the Cafe de Fa, “Cocorico, la France!” “The coq is crowing! Wake up France!” Yes, but they are already more awake to the extremity of our human situation than the Americans, where the urgency gets more extreme by the moment. Many French people believed that the results of our last election would cause a general uprising and a re-creation of our democracy. Yes, that was the possibility. Is it still? Cocorico Etats-Unis!