Stanley Stephen Pashko only became a father when he and his wife adopted me. A strange opening sentence. Who thinks of fatherhood this way? He was thirty-nine at the time and had already lived a lot of life.

I was remembering the feeling deep inside my chest I can mine from the earliest days of my memory, probably the days when I played in the basement while he pounded away on his typewriter between my demands. It was a warmth, an energy that powered my legs as I rode my tricycle around and around the big basement. It was the way, later, I began to identify that mysterious feeling of love. My mother was a constant. I barely remember what she was like in those times. Maybe the smell of that warmth of perfume that blanketed me as she hugged me goodnight before going out with my father to the ballet. Or the figure standing on the sidewalk watching me toddle off a few yards only to turn and smile and unsteadily waiver back.

So–his life before. From where we stand, the life of a parent is only visible from the moment of our consciousness. Like an iceberg, the greatest portion of what went into the creation of that person is hidden below the dark water. I knew it from those black and white square photos, stuck to the page with black corners like the corners of an ornate picture frame. A thin, young man, with thick, wavy dark hair in the style of Cary Grant, in a camp in the Adirondacks, in a rowboat at Lake George, with friends in the sun in Province Town, with his arm around my mother, horsing around with her on a tennis court, striking poses, playing ball on the grass with an unknown little girl on Cape Cod. In the photos, you don’t notice the limp. I know this life from the stories told around dinner tables with Jewish relatives and glasses of purple Manischewitz or late at night on the sofas in the living room, just him and me.

When I was a little girl, almost every Easter and sometimes around Christmas, we went to the town where he’d grown up. We went to visit my Polish, fat and wonderfully aromatic grandmother. Olyphant, Pennsylvania. A town where Anthracite coal, hard and clean burning, had been mined since the mid-nineteenth century.

Olyphant was seeing the peak of production when my father was born. The other kind of coal–soft bituminous coal, first from the mines of Britain and Germany and then from Virginia–had begun to achieve popularity as a fuel when Americans had finally cut down most of the forests for wood to burn in their stoves and to make charcoal for manufacturing iron. Anthracite, since it’s harder to light, had to wait for its fluorescence until some bright inventor in 1860 developed a way to construct iron grates to hold it, allowing air to circulate above and below, feeding its bed with oxygen. With a widespread education effort, it finally caught hold as the fuel of choice in the cities of the East Coast. For a while, it became the dominant source of energy. Production boomed a bit during the First World War when soft coal wasn’t available from Europe and almost came to a halt during the depression when John Lewis lead strikers to gain higher wages and benefits and prices went up.

When my grandmother arrived in America around 1890, an eighteen-year-old Polish woman all on her own, fleeing poverty and waves of Russian invasions accompanied by raping and killing, mining was starting to boom in the town. Poles and Russians were beginning to supplement the supply of the Irish who had come to mine earlier in the century. By the time we started visiting in the 1950s, mining in Pennsylvania had dwindled to a near standstill.

In her Polish neighborhood, not much aside from the bustle of a mining town seemed to have changed over those years. St. Patrick’s Catholic Church still dominated the area. The wooden stairs led up the back to her two floors of the wood frame house on the main street, with a little general store and apartment for old Mr. Jagelewski and his wife downstairs. Central School still stood, a few blocks away, gray and flatly austere.

She had married a Russian coal miner a few years after her arrival. To supplement his income from the mines, she ran a boarding house and saloon. By the time my father was five years old, he was entertaining customers by standing on the bar and singing. He played on the dirt streets and back gardens and ran errands to the store down the street for his mother. The town was dominated by coal in those days. The Lackawanna River ran yellow with sulfur. Like dark hills behind the houses of the main street, small mountains of coal slag sent up faint curls of smoke by day and glowed like fire and brimstone by night. Families waited for the return of the miners in the evening when they’d gather around kitchen tables, faces black with the coal, and drink each others’ health with shots of vodka while wives fed them pierogi and stewed chicken.

One day that year he was five, playing on the street with friends, hoping for a ride, he climbed up on the back of a milk wagon, stopped to deliver some milk. The driver returned, jumped into the cab without seeing the little boy on the back, and clicked his horses into motion. Somehow, the boy had gotten his foot stuck in the spokes of the rear wheels. As they began to turn, his leg was twisted completed around, mangled and broken, before his screams reached the ears of the driver. People rushed up, pulled him free and carried him to the doctor down the street. There the doctor examined him and pronounced the leg impossible to save.

By that time, his father, having been informed on his way out of the mine, had run from the mine to the home of the doctor. He insisted the leg be saved. It was–after multiple long surgeries, infections, weeks in bed and a childhood spent in recovery. Ironically, it was one of the things that gave my father the means to feed his keen intelligence. Laid up, he devoured book after book from the little library in town, reading every book cover to cover by the time he’d reached high school age. The other track it etched in the course of his life was the deep furrow made by the flow of the copious amounts of vodka he used, starting from the age of sixteen, to medicate the constant pain from a knee where bone ground on bone.

His experience of the Great Depression had been dramatically different from that of the woman he eventually married. Her life had been relatively sheltered from the impact. Having graduated from Central High School as a virtual autodidact, attending school mainly for the exams which were hardly a challenge, he scraped by with his family into his twenties. Even before the Depression, things were hard.

One late night, vodka in hand, he told me a story from those times. When he was twelve or thirteen, they had no money to buy the coal they needed for the big coal stove in the kitchen that cooked their food and heated the house. His father had died in a cave-in in the mine. His mother had remarried. His step-father would take him and his younger brother, Mike, to abandoned mine shafts. While the boys waited at a short distance, he would light a charge of dynamite, throw it down into the hole and run like the dickens to where the boys were crouching on their haunches. A big explosion, spewing dirt up through the hole and bulging the ground under their feet. They would wait for a few minutes, gathering up a length of sturdy rope and a burlap sack they’d brought with them. As the dust settled in the opening to the shaft, one boy would tie the rope around his waist. After pulling the knots tight, their step-father would wrap a scarf around the boy’s nose and mouth and tie it in the back of his head. The boy would then slide over the edge of the hole while his step-dad, hanging on tight to his end of the rope, slowly lowered him into the dust of the shaft. The boy would hold his breath and, when the shaft opened up towards the bottom, would swing the burlap bag around his head for as long as his breath would hold. A jerk on the rope would signal to pull him up double-quick. The two boys would take turns clearing the dust this way until it was possible to breathe in the shaft. Then they would be lowered to the bottom with coal buckets and a coal shovel. They filled the bucket with the coal the blast had loosened and then signaled to be pulled up. With a heavy bucket of coal each, they’d make their way back home as inconspicuously as possible with the stolen coal, the boys staggering under the weight.

At some point in his early twenties, he started meeting with the men of the United Mine Workers Union and studying Marxism. He never really spoke about this period except to say that he was a labor organizer in his youth. Someone in the Union eventually recommended him to Brookwood Labor College in Katonah, NY.

Brookwood was a unique place, originally founded to teach working-class teenagers non-violent approaches to social justice and political change. Yes, in the early 1900s social justice was on the minds of a lot of middle-class idealists and working-class unionists. It’s not new. After a few years, the tuition-free school was struggling and decided to hand over management to a bunch of union activists who believed a new social order was needed and was, in fact, on its way. The workers were the ones who would usher in the change and education would help to make the change non-violent and gradual.

Since he only spoke about “going to a college for socialists” once or twice during those evenings drinking beer on the patio or vodka in the living room, I have to reconstruct those years from the bits and pieces. He studied maybe a year or two there, going through the books in the college’s small library the way he had in his hometown.

The one thing I know for certain about this experience was that he went on the road with the Brookwood Labor Players theater group. I’m clear about this part since, at every chance, he would do his “villain” routine, turning his back on his audience of one or two unsuspecting children, and then, turning quickly towards them, eyes glittering, bushy black eyebrows brushed down, would give them his throaty, threatening, theatrical “Ho ho my little friends”. It must have been the part of the nasty mine owner. Used to embarrass the heck out of me. He toured Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New Jersey and Maryland with plays like “Miner” and “Sit Down” (which portrayed the Flint sit-down strike of 1936-37), some of which met with critical acclaim. He may have stuck with it until the college closed in 1937. An interesting and neglected crack in American history. Too bad the idea of social justice and a movement led by workers never really caught on.

He moved to the city then and got what work he could in publishing. He worked for a comic book outfit for awhile before the war, was a court reporter (learning the Gregg shorthand he modified and used for all his notes and typing 120 wpm on a manual Royal typewriter) and worked his way into a job at Random House. Since he had a 4F deferment from the Service because of his leg, he put in his time working in the shipyards in New York until the war ended and he could return full-time to publishing.

I can imagine him during those days, smiling at the boss, smart as a whip, but quietly unwilling to buy into the system. As time went by, he, like many of those who had found the values of socialism so attractive, was completely disillusioned and disgusted by Stalin’s rule. Living through the McCarthy years brought him outrage and conflict. Friends were not able to work. He had torn up his card years before.

He met his young Jewish wife in his late ‘30s in Brooklyn and she began his “cultural education”, smoothing out his course places with trips to the ballet, the theater, and the opera. By that time, he had begun to write a few articles here and there and had plans for a novel.

The year they married, he was promoted to an editorial position at Random House, the only non-Jew in a circle of my mother’s intellectual friends. She showed him off. Drinking just fit in with being a writer. He held forth well in their company. They went to rent parties in the city with people who would become famous authors and illustrators. They spent summers in the Adirondacks with art friends who had started a summer camp to promote the arts and sometimes in Cape Cod with artist friends from the city. They had rollicking good times. He was infamous for having burping contests with one of the local artists in Cape Cod. The two of them would chug those old glass bottles of Coke and then see who could let out the biggest belch. They were given paintings and threw parties in return. Things went sour with Random House and a friend got him a job with the thriving publication, Boys’ Life, the official Boy Scouts of America magazine, as his wife went through a series of miscarriages.

When they decided on adoption, he had already started a series of books for boys including “An American Boys’ Omnibus”, “The Complete Book of Camping”, and “A Boy and His Dog” with my mother as his editor. They were living in a small apartment in Flatbush, Brooklynn. The year before they adopted, he finished a collaboration with her called “An American Girls’ Omnibus”. She was always a bit sore that he didn’t give her co-authorship, saying it would sell better under his name. He, for his own part, was always a bit embarrassed at being employed by the Boy Scouts as an editor. It was a come-down from the literary world of Random House.

For years he wrote the responses to boys’ letters to Pedro the Donkey, the Boy Scout mascot, thereby becoming the personification of Pedro himself. He used to joke to friends that he got the job because they all knew he was a “horse’s ass” anyway.

After they adopted me, he took off a year or two from “the business” to freelance. He wrote on a Royal typewriter (see my story in the “About Me” tab of this blog site) and banged out the rest of his thirteen books for boys, many dedicated to his new daughter. He wrote at least ten pages a day and approached writing with the attitude of someone used to work.

He allowed people to believe that he had pressured my mother to give me a boy’s name since, working as he did for a boys’ magazine, he must really have wanted a boy. It was our secret that it had been no such thing. It was the name my birth mother had given me and my mother, against his advice, decided to keep it. Our conspiracy about this myth was one of our bonds. He stuck up for me later during the barrages of my mother’s protective nagging. I was lucky that way.

Later, when he became the fiction editor of the magazine, he had his revenge on the literary world by developing relationships with Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and Arthur C. Clark and getting them to write stories for him. He somehow also got Pearl S. Buck, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Bobby Fisher and Robert Heinlein to contribute. These are only the famous authors I know for certain he solicited as fiction editor. There were probably many others.

By that time, we’d moved to New Brunswick to follow the offices of the magazine. He would drive into the city where he and Isaac Asimov would drink together and swap stories. My father would cheer him up.

He went on “story assignments” with Ansel Adams into the southwest landscapes and came back with magnificent photos for spreads in a magazine that also specialized in dumb cartoons and jokes and stories about how to earn your Atomic Energy Merit Badge. He also was drinking more and more, hiding his bottles from my mother, forgetting where he put them and getting everybody sloshed with double shots at the parties they threw at the house they’d finally bought in Princeton. By the time they had a teenage daughter in the house, things could get pretty interesting later in the evenings.

The deep love my father and I had for each other became clouded by the depression of alcoholism and the railing of a teenager of the 60s at the injustice of a system he had never wanted. But it was still there—that deep bond. He was a man of an intensity of understanding, a profound and romantic heart and a large mind, all kept close in by layers of pain at the last until, minus the romantic heart, it was released by drink.

The only time I ever saw him cry was when, at the age of eight, I came around the corner into our little kitchen to find him leaning into the crook of his arm propped against the refrigerator, weeping. He had just learned his mother had died. His eyes filled with unshed tears the day I came home from an abortion and he sat beside my bed.

He saw his granddaughter once when she was nine-months-old. There is a photo of him at the dining room table of the house he had abandoned and left to my mother, sitting with the baby on his lap. His eyes were wet. He is terribly thin, even thinner than in the photos of his youth, but with pale, pale skin. We laughed at his corny jokes and at the baby.

At the end, having left his wife to protect her from what he had become, he died of complications of cirrhosis in an apartment in a small town in New Jersey, surrounded by beautifully made oak bookshelves, full of the books he treasured, alone with them and his memories of a mother and daughter he’d loved while feeling unworthy and a wife he had struggled, and in the end perhaps failed, to love.

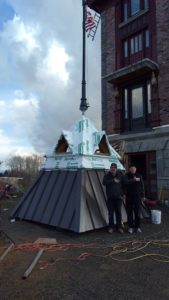

Art and Margaret recognized it as a piece salvaged from one of their college campus renovation jobs. They speculate the guilt must have been eating him all this time. It now sits like some bizarre monument in front of the house, a complement to the flag pole pyramid. Even with all the hours and hours of construction spent up on the roof through the winter weather, building things and then tearing them out to satisfy the City, they have now, at last, been able to mount clock faces on the four sides of the tower. They are all permanently set at 10:04. Evidently, no lightning strike was required to stop time at that precise moment, but who knows what the future might hold when we return to it, yet again.

Art and Margaret recognized it as a piece salvaged from one of their college campus renovation jobs. They speculate the guilt must have been eating him all this time. It now sits like some bizarre monument in front of the house, a complement to the flag pole pyramid. Even with all the hours and hours of construction spent up on the roof through the winter weather, building things and then tearing them out to satisfy the City, they have now, at last, been able to mount clock faces on the four sides of the tower. They are all permanently set at 10:04. Evidently, no lightning strike was required to stop time at that precise moment, but who knows what the future might hold when we return to it, yet again.